The Swamp & The Monster

What DreamWorks' Shrek has to teach us about media enclosure and a content culture

DreamWorks' debut movie Shrek has become something of a cultural, and an online, landmark; in my mind, for all the wrong reasons. Giving a quick 'google' for Shrek allegories, one is bombarded with a near endless barrage of leftist psychobabble; Shrek is Marxist, Shrek is about systemic racism, Shrek is about totalitarianism, Shrek is about Margaret Thatcher, Shrek is about trans rights. All ridiculous, all wrong. This week's lighthearted essay will be a short introduction to all the right reasons to watch, and talk about, Shrek.

At first glance, Shrek is a classic fantasy story, if perhaps told from an unusual perspective. Ogres, Knights, Dragons, and a missing Princess in need of rescue; an ode to traditional fantasy storytelling. Yet in the background, there is a much more sinister plot in motion, and included within it, a deep critique of corporate power in contemporary America.

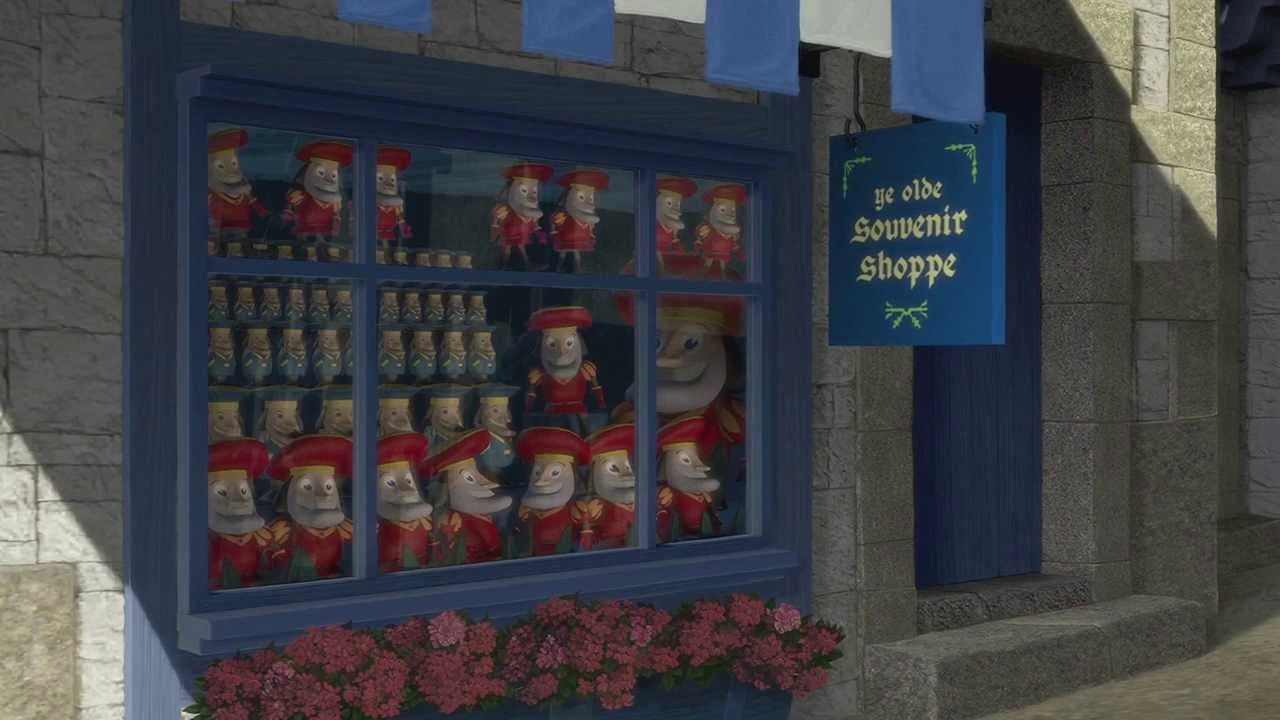

Lord Farquaad, or as is clearly alluded, Lord 'Fuckwad', reigns supreme over the Enchanted Forest, where Shrek resides, from his castle Duloc. Duloc is strange for a castle. It has a huge parking lot for carts and carriages, velvet ropes guide visitors through tollway gates, and the streets are lined with animatronic displays, souvenir shops and bobble-headed mascots. From his throne, Lord Farquaad has ordered his troops to round up and imprison all of the fairytale creatures from the Enchanted Forest. Shrek, though, our reluctant protagonist, wants more than anything to be left alone. Unfortunately, life has other plans for Shrek, who's swampy abode becomes a refuge of fairytale creatures, rounded up from their homes by Lord Farquaad's men. Shrek becomes Farquaad's champion in search of his would-be bride, and we all know the story from there.

The story we don't often notice is the story that sets this plot into motion. Two facts illuminate; DreamWorks' early staff were largely made up of former, and disgruntled, Disney employees, while Lord Farquaad's appearance is said to be based closely off of their old boss, one-time Disney CEO Mike Eisner, with a height swap to make him a Napoleonic ‘manlet’. This should bring the allegorical undercurrent of the story clearly to light.

Lord Farquaad, Disney, from Duloc, Disney World, are rounding up the fairy tale creatures of the Enchanted Forest and removing them from the commons, to herd them into reservations where they will be owned and controlled by Disney, just as Disney rounds up the intellectual property rights associated with old folklore, copyrighting stories and characters with movies that remove those tales from the creative commons. Essentially, owning the cultural heritage that produced the characters they adapted.

Of course, this isn’t what Shrek is ‘about’, Shrek is a children’s adventure movie; and a pretty good one, at that. It holds up for a reason. But this underlying critique is true, it’s real, and in many ways it helps explain a kind of cultural fatigue, a malaise of content that so many people today are experiencing. Morgoth touches on this feeling with incredible prescience in his latest video essay, as he is really the final king of the internet video essay, The Great Turning Away.1 A small handful of people control almost all of the stories we tell today, owning their rights and dictating the direction and frequency of their production. These people are not artists, they are not poets or aesthetes nor are they concerned, really, with transmitting your values to those watching. They are concerned with two things; a never-ending stream of money, and promoting a culture which is increasingly atomized, in which more people will become passive consumers of content.

Shrek’s critique should bring to the fore questions about what kind of society we want to live in. To what degree do corporations have the right to own the traditional stories of our cultures? To what degree does a small group of people have legitimate claim over such a huge swath of all media? If we believe in dispersion of power, perhaps media companies should be limited to a certain number of intellectual properties to operate, rather than allowing a handful to own nearly the entire landscape.

Auron MacIntyre has brushed up against this topic in two of his latest podcasts, one of which I discussed on a small Twitter thread, where he dissected a New York Times review of the latest Little Mermaid remake. In his recent interview with Inez Stepman, Auron and Inez covered reasons for the failure of previous conservative boycott movements.2 Chief among these reasons was the partially concealed corporate monopoly over many of our marketplaces. Whether it is Kellogg's hands in nearly all cereal products, or something like a fourth of all products in the grocery store - or Disney's control of children's media, parents are either left with no real choice, or a choice between an identically aligned handful of suppliers.

Whether we undertake the task of creating parallel economies, retaking the institutions, or total exit - or some mix thereof, we must understand that like Shrek, a desire to be left alone will not stop the march of our enemies; it can only ensure the eventual arrival of bigger problems right onto our doorstep.

Thank you for reading Position & Decision! I know this post is, in theme and tone, a bit different than my usual writing. I hope you enjoyed a lighthearted attempt to broach the topic of limiting intellectual property and ownership of the commons.

In the next few weeks I'll be returning to Jünger for a book review of On the Marble Cliffs, and in addition we should be seeing the debut of my second here, L.Q. Bucellarius, who you can now find posting original prose and poetry on his Twitter.

https://youtu.be/nMKDVEha2kg

https://www.youtube.com/live/wwAtuG3e1Ic?feature=share

Very fun essay. Our cultural heritage IS in the hands of corporations...

This was very good but i feel it ended all to upruptly. Never thought I'd ask this but do you have more to say about Shrek?