This essay will attempt to weave together two somewhat distinct but deeply interconnected problems in political philosophy which I have seen expressed in the last few weeks. The lack of understanding of these foundational differences contribute to a misunderstanding of theoretical faction and of real political action. While both problems are conceptual, it must be said that one comes before the other and so we will start with that, which deals with the natural state of man. A point we may return to is that I believe these problems lay at the heart of divisions among the Right today, and so contribute to its inability to understand itself or to present a united front, if there is one.

This first issue is the issue of human nature, or to be more precise, the natural disposition of men. Throughout human history, thinkers and statesmen have lined up on two fundamentally opposing sides. The first we might call the Homeric side, or the Heraclitean side as I have said to my friend Athenian Stranger. This side holds, as Heraclitus did, that fundamentally the world is a world of movement, or that is to say of chaos. In this world of change and instability a man must be his own anchor, his own oar, his own vessel and his own port. Power then defines human life and therefore defines human relations. The good man, the fine man, the high man, is he who is able to muster will into being and to subject onto the world his desires, to cut out from the world an order held by blood and steel. Allusions to Homer, Thucydides, are clear. We can trace this understuff of human understanding through to Machiavelli, to Hobbes, to Hume, and to Nietzsche.

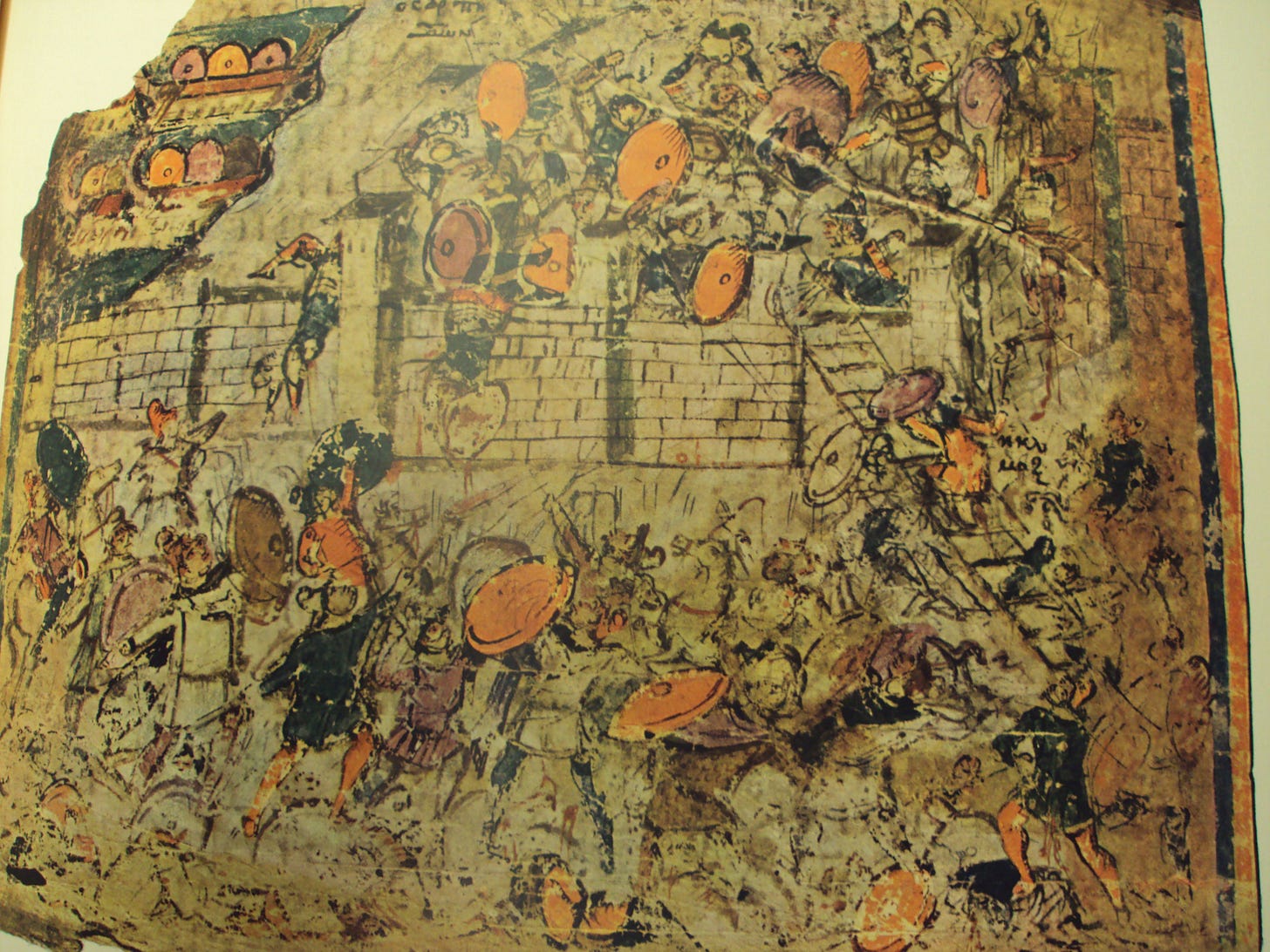

In opposition to this view of nature is what we might call the Aristotelian side, though among his ranks we can include Saint Augustine, Saint Thomas Aquinas, the great poet Dante, and near the whole of the Christian Political Tradition. In this view, man arrives in an ordered world, a world laden with meaning both in nature and in human social life. There is a teleology to that which we find here, where those things among the world have purpose, where man’s soul is negotiated between appetite and reason. This teleology supposes that we live towards a human goal of Goodness, Virtue and Eudaimonia, or that kind of happiness which comes from a virtuous life. Best of all, of course, is when it is lived well in the virtuous community. This vision of human life as negotiated in community, as built towards higher virtue, is built on top of a vision of nature that sees peace as the norm and violence as the aberration of that norm. This is understood not because of a claim that violence is not common, but because of a teleological view of the world in which there is an ordered universe and therefore an order among men and a goal of human felicity that turns toward peace.

Now that we have established the divide it becomes important for us to articulate the posture of those two sides before we argue the second question. By and large, what we see is the dominant position of the Heraclitean Camp in the pre-socratic age, and then a revival during the Renaissance and the Early Modern period. In contrast, we see the string of Aristotelian thinkers arise in the wake of the second Peloponnesian War with Aristotle, and reign until the Religious Wars and the breakdown of Christendom. Once said this way, it becomes easier for us to understand exactly why the thinkers are clustered so peculiarly - either bookending Western history, or wedged in the middle.

And now to our second concern, which conceptually deals with the secular frame, the way we discuss ‘religion in politics’ and the short example of Cesare Borgia. The fact that this point needs expression came during a recent Twitter Space between a few of those actively engaged in philosophical dialogue in that online community. During the space, Athenian Stranger was asked a question about religious perennialism, or the idea that, all or many religions being so similar in fundamental claim or in respect to command, that they all are in some sense the same and are simply different peoples’ expression of some kind of universal feeling or urge. A critical problem for perennialism of this kind is that it is so absorbed by a view of the world being shaped by power that it refuses to contend with the most basic part of religion which is that it is, fundamentally, a superstitious claim to true reality. That is, that it does not see itself as imposing onto the world order but actually to be recognizing the very order that the world is shaped in. In contrast, it is ideology which seeks to scaffold up a system by which men can create a utopia where peace is maintained. The intense cynicism of our age, produced by people like Hobbes and Hume who sought to articulate a world where fact and value (expediency or efficacy and morality or custom) might be utterly distinguished from one another, has created a secular frame so dense that we cannot conceive of people who do not operate outside of it. The ‘Realist’ school of foreign policy, common in the United States, operates precisely under this frame.

This problem is inflamed when we attempt to discuss history, particularly medieval history, because it relies on two premises of modern secular ‘power politics’ that are not true of the medievals. The first is that although we understand religious people today, we understand them by viewing them as people with religion as a personal ideology. This was not the case for the medievals, who lived in a society that was Christian. They were not religious, per se, but they lived in Christendom. Their whole social organization took Christendom to be true at the level of reality. The second inflammation is that in Christendom, therefore, sovereignty itself does not exist.

To flesh out these ideas I will be working with some quotations from Andrew Willard Jones’ fantastic Before Church and State: A Study of Social Order in the Sacramental Kingdom of St. Louis IX.

[T]he assumption that underpins the modern understanding of politics, the assumption that leads us to see sovereignty as always historically relevant, is the same assumption that underpins the doctrine of the secular… the existence of primordial violence.1

And this conception arises, Jones aptly notes, from the understanding of the world derived by way of the Heraclitean camp, which itself creates the conditions necessary to invent or ‘discover’ sovereignty.

In the face of perpetual violence, peace is possible only through the imposition of a greater violence that can suppress all other conflicts. Sovereignty allows for legitimate violence. Without it, in the modern world of ubiquitous violence you can either accept political nihilism: the strongest will rule and there is no right or wrong about it— this is the route taken by many postmodern theorists. Or, you can assert that all violence is immoral and that therefore all government is a crime… Or, you can maintain that sovereignty is real and has existence prior to any particular, historical political situation. The sovereign is that power that can wield violence legitimately…

It seems to me that almost all modern political thought, from theories of the divine right of kings to theories of representative republics, are ultimately about who is sovereign and how their monopoly on violence can be realized most efficiently.2

In contrast, of course, Christendom held the opposite of the state of man before God and so did not experience the creation of sovereignty or in the dual realms of secular and ‘religious’.

We must abandon the assumptions of modern politics ultimately because France [in the thirteenth century] was a Christian kingdom and, within Christianity, peace is the primordial condition and violence is sin, an aberration, a corruption, and ultimately something that does not even have a real being— it is an absence. This is a key theme of St. Augustine’s thought. St. Thomas Aquinas treated peace as the final end of being itself. One of the things we have to allow for in order to break free from the modern construct of the “problem of Church and State” is that charity could have real content as charity, that self-sacrifice is real and not just a tactic of conflict. We have to allow for the possibility that two people can have a relationship that is not predicated ultimately on competition for power, one over the other— in effect, we have to allow for the possibility of non-dissembling peace. If we do so, we can understand the people of the thirteenth century on their own terms, within their “complete act,” because this is the language in which they speak.3

I want to take a moment here to give Jones’ book my highest recommendation, and a commendation on its success in presenting to us a vision of the people of Christendom in the way they saw themselves, and not in the way that sociologists have dissected them since the rise of the modern era and its domination by the Heraclitean view of politics. I could do, and probably will do, a more in-depth review of the body of the book on this blog in the future, but I think we have enough for now to turn to our final example, the life of Cesare Borgia.

I’ve chosen Borgia for two reasons, one of which I will share and the second of which I will leave to be surmised by my wonderfully thoughtful readers. The common critique we hear of Borgia today is that he was guilty of politicizing the Church. The Borgia’s are often hit by this accusation. Of course, Cesare’s father was Pope Alexander II, so it really invites itself. The problem is that this is not an explanation for Cesare Borgia’s unpopularity because it is not an accusation which would have made any sense, perhaps until the wake of Machiavelli. What would it even mean to make the Church political? Of course the Church is political. If politics is about living and governing and the Church teaches the truth and undergirds society with respect to each, how could it not be? How could charity not be political? Education? The Crusades? No, Cesare Borgia’s crime was not in making the Church political but in disturbing the Peace and the Faith by making the political in the Church devolved from truth and into appetite for the collection of power for its own sake.

We live, it should be clear by now, in a world constructed around the near complete victory of the Heraclitean view of political life. But this was not always so, and it may not be so again. To live differently and to build differently, it is important to demarcate and to understand the Aristotelian view not merely as an academic exercise but as a civilization which ran a course of a thousand years. In that that civilization there was not mere power that produced human flourishing, happiness and salvation, but a business held in common; not commerce, but the business of the Peace and the Faith.

Jones, Andrew Willard Before Church and State: A Study of Social Order in the Sacramental Kingdom of St. Louis IX, 2017. Page 13.

Jones, Andrew Willard Before Church and State: A Study of Social Order in the Sacramental Kingdom of St. Louis IX, 2017. Page 14

Jones, Andrew Willard Before Church and State: A Study of Social Order in the Sacramental Kingdom of St. Louis IX, 2017. Page 19

The Primacy of Peace is one of the most fundamental disconnects between everyday acts and living the Faith. All the time I hear people say, "Yeah, he messed up the group, but it was the right move for him," or "From a game theory point of view..." or "How can that be enforced?" Each of these examples presumes that man's nature demands looking out for number one, and each example fails miserably when put in the context of familial love. Christendom, to the extent that it was actually Christian, was the extension of that familial love to all political relationships. Thank you for the article!

This is fascinating and worth meditating on for a long time and deeply.