Over 5,000 years ago, men and women on the Orkney Islands built 20-foot tall megaliths. 2,000 years later, they were still building stone greathouses with slow stone roofs or high wood ones. 500 years later, they were gradually buried and slowly forgotten. 2500 years later in 2003AD, a Farmer’s tractor got caught in one of those buried stones and began a 20 year journey of excavation and discovery.1 In 2024AD, they were buried again. Some in 2025AD remain open to be explored, and in them, a visitor wonders “Who’s home was this?” That question is one all peoples—perhaps especially Americans—have to ask themselves when old stones are uncovered in their own homeland.

For the people of Orkney, these sites are places of pride in being Orcadians. Looking upon something so ancient reminds them that they are inheritors of a land that still beats to rhythms recognizable to the ancients: the long dark winters, the return of the summers, the air’s smell and the grass’ feel. However, nothing could be more alien to them than these ancients. The greathouse “Structure 10” was built in 2900B.C. and when destroyed in 2500B.C., it was filled with rubble, ash, and rotten refuse.2 Within its hearth, an inverted cow skull. Other artifacts feature art and runes that archeologists could only speculate on, and the wise ones do so reservedly. While the stone sites are sources of pride and heritage for the Orcadians, they are not the same folk—but inheritors of the same place.

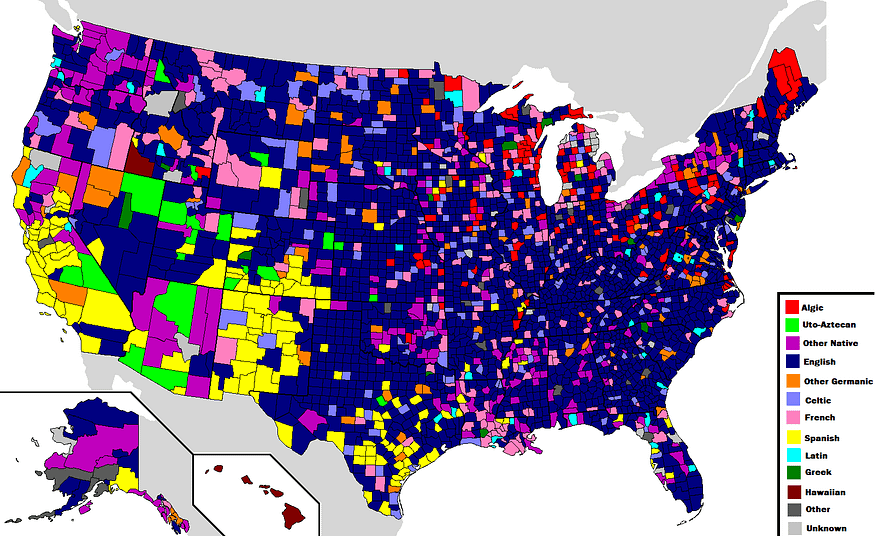

In the United States, archeological discoveries of any comparable age reveal indigenous dugouts, poles, or burials. The indigenous survive today to lay claim to them as their heritage despite being similarly a transformed people. No White or Black American could make a similar claim, both being descendants of willing or unwilling colonizers of the land from the past four centuries. For them, their ancient heritage really harkens back to a bygone land that too has changed since their ancestors’ departures. Most of the United States, for them, was settled much more recently within the last 200 years by their own peoples.

Americans, then, can hardly look upon their own home and feel a solemn connection to Neolithic ancestors that once walked the grounds of New York, Iowa, or California. Americans sometimes even dismiss that they have a culture to be identified with (though any American that travels abroad will immediately sense they are no chameleon at all). And while Americans are immediately identifiable to foreigners, Americans are fascinated with finding a sense of ancient identity. They invest in genealogical studies, DNA samples, or even a sliver of (supposed) indigenous American ancestry to somehow lay a claim to a much older heritage.

The true answer to this question is actually quite simple and unmagical: that Americans are both distinct and share their heritage with their ancestors be they Italians, Africans, English or otherwise. They brought with them some traditions to be adopted and changed in their own new land.

Nonetheless, a theme of being a people exiled touches every major group of Americans. The White Americans identify with being the men of “the West” with connections to European culture and history should they Puritans fleeing the Church of England, Irishmen fleeing famine, or some other people seeking prosperity in the “New World.” Black Americans are descendants of slaves, sold from the coasts of Africa to serve another exiled people. Even the indigenous wrestle with their own history of their homelands being occupied and themselves sent to some other place reserved for them. And so on, people rarely express they are people of ‘this land’ in particular.

Americans are not unique in this. Indeed, every people that exists today can be said to merely occupy the land in which they stay—should one look back far enough. And yet, we can identify a very old place uniquely called ‘England’ even if the English map itself is dotted with cities that point to a varied cultural map.

Every land is inherited and every people inherit, by conquest or birth, to struggle in a place. When the Israelites were scattered into exile, far from Zion, they spent a relatively short time (perhaps 70 years) before being allowed to return and rebuild. For the Americans, there was never a return—America was to be theirs forever. It built cities named first after Britain, then indigenous and Spanish names. All of it conquered and inherited and spreading the religion of an ancient Israel rooted 4000 years ago, inheritors of the religion of Jesus the Christ.

Exile is something painful, to feel as if one does not truly belong where they are. The American anxiety over identity speaks to this mourning; that Zion is elsewhere and they are away in some other people’s land. To make peace with this anxiety, the American should understand they are inheritors and while the ancient homelands are a part of their story, they are still writing a new one. The ancient Vikings that carved graffiti in Orkney’s old stone tombs (made thousands of years prior)3 also migrated, becoming Christians, and probably were the first Europeans to visit North America. To enjoy an affection for Irish folk can hardly be considered disingenuous when elements of it are as much exports of Americans as they are imports from Ireland (such as one of my favorites—Finnegan’s Wake—was written by Americans in 1864.)4

To journey abroad then is something of a spiritual pilgrimage, too look upon ancient stones and recognize where ones own ancestors once struggled and lived. It does provide identity and belonging. However none, not even the Orcadians, can cling to such sites as truly their own. Indeed, much of it had to be reburied lest it disintegrate forever. They are new Orcadians, Christian and British. Their restless spirit does not rest in the ruins but in the season God created for them. The American regime, as much as it would desire, cannot offer this rest either.

Those exiled from Judah did not long to return home and rebuild the kingdom for its own sake but for the sake of worshipping God at His temple as He asked it to be. The faithful exiled recognized that only the Way of God offers them their identity and belonging in the end. It is that worship that maintained them through captivity, to be among the Assyrians and Babylonians but never one of them.

So then, for the American conservative to be wringing their hands over if they belong in their own land is to be tempted to idolatry. It is the land for Americans, and yet it feels like it may just be for anyone. The land was once not theirs, it is, and perhaps soon to be sold to another people. But within all this tumult, the words of Jeremiah to the exiled Judeans cries to them what they must do in a land that does not feel theirs:

“Thus says the Lord… Build houses and live in them; plant gardens and eat their produce. Take wives and have sons and daughters; take wives for your sons and give your daughters in marriage, that they may bear sons and daughters; multiply there and do not decrease. But seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you into exile, and pray to the Lord on its behalf, for in its welfare you will find your welfare.” (Jeremiah 29:4-7)

Ross, Peter. “What Scotland’s Old Stones Know.” Smithsonian, Feb. 2025, pp. 40–53.

Ibid.

Ibid.

“Finigan’s Wake; Popular Irish Song / Historic American Sheet Music / Duke Digital Repository.” Duke Digital Collections, repository.duke.edu/dc/hasm/b1044. Accessed 11 Jan. 2025.

A nice complement to this article is Martin Heidegger's Memorial Address, specifically his exploration of autocthony and modernity. These both point to the inherent tension between a country founded on principles versus a country founded on ethnicity / religion / culture.

https://www.beyng.com/pages/en/DiscourseOnThinking/MemorialAddress.html