“What would it now mean for a contemporary man to take his lead from the example of death’s champion, of these gods, heroes, and sages? It would mean that he join the resistance against the times, and not merely against these times, but against all times, whose basic power is fear. Every fear, however distantly derived it may seem, is at its core a fear of death.”1

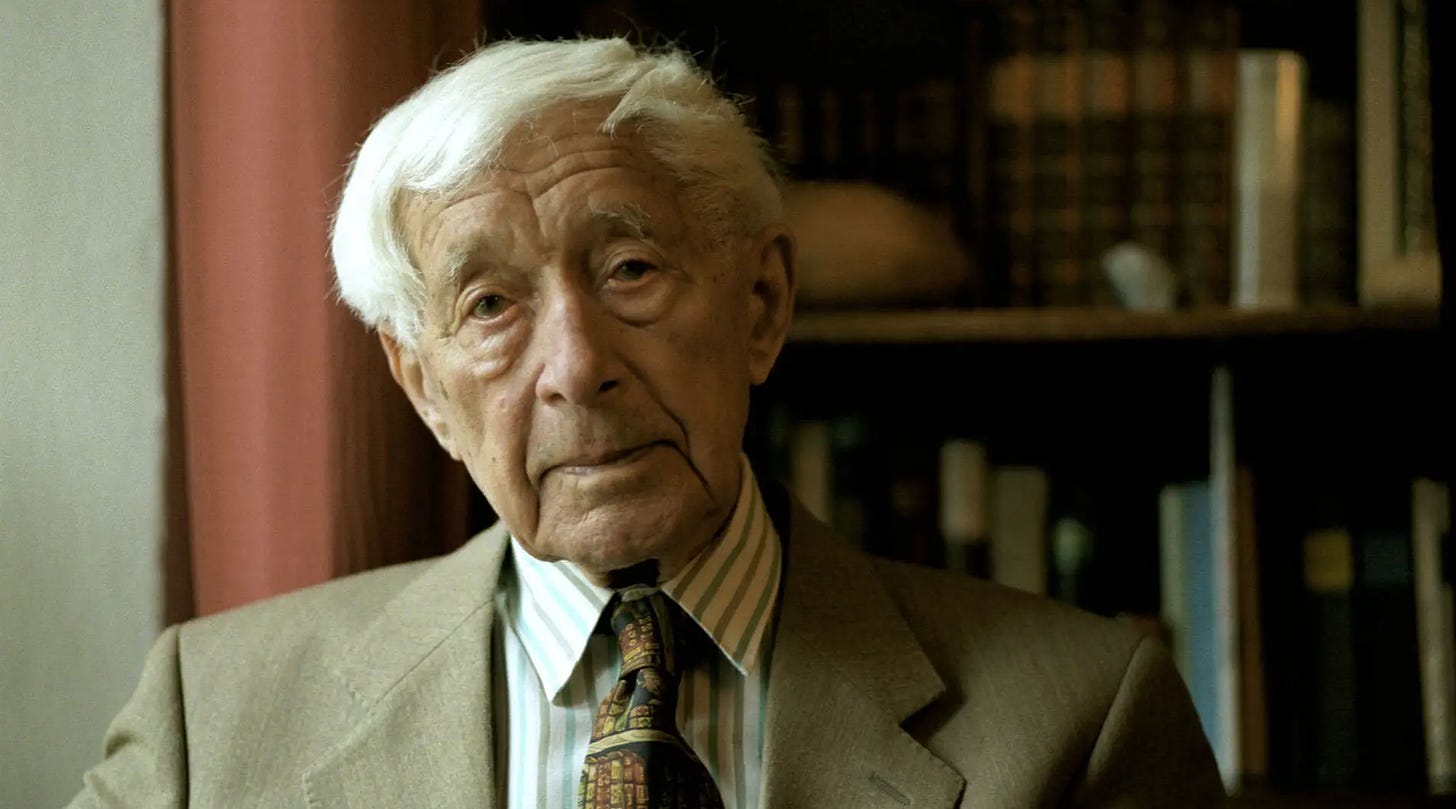

Today is Jünger Day. Born in 1895, Ernst Jünger led a life of incredible — as overused as the word is, I do mean it, incredible— adventure. A spirit with as much heart, soul, drive, and love as expressed by a thousand men. He is an inspiration to me and his thought remains a cornerstone of my own understanding. In many ways, he is the standard of a life well lived, through hardship and pain, to greatness and on to peace. Today we will take some quotes from his 1951 essay, The Forest Passage, and discuss.

I chose this essay because it is a call to be answered for individual action. In my first three posts, we’ve gone into some detail about how to understand, frame, and interpret the social realities which are playing out around us. My answer in each, to some understandable disappointment, was that we must prepare ourselves to confront the storm, and to pass through it. To exit. To unplug. To discern and decide for ourselves. The Forest Passage is Jünger’s blueprint for exit, a handbook to explain its necessity and guide our thinking, and to steady our hands. But enough from me, it’s Jünger Day.

[T]he growing automism is closely connected with the fear, in the sense that man restricts his own power of decision in favor of technological expediencies. This brings all manner of conveniences- but an increasing loss of freedom must necessarily also result. The individual no longer stands in society like a tree in the forest; instead, he resembles a passenger on a fast-moving vessel, which could be called the Titanic, or also Leviathan. While the weather holds and the outlook remains pleasant, he will hardly perceive the state of reduced freedom that he has fallen into. On the contrary, an optimism arises, a sense of power produced by the high speed. All this will change when fire-spitting islands and icebergs loom on the horizon. Then, not only does technology step over from the field of comfort into very different domains, but the lack of freedom simultaneously becomes apparent— be it in a triumph of elemental powers, or in the fact that any individuals who have remained strong command an absolute authority.2

We find ourselves on this train now, but not in control. Jünger’s descriptive mastery is on full display in his articulation of the spirit feeling of technological empowerment. It is like moving quickly, it is like a propelling force, but easy. But on rails.

Where the automism increases to approaching perfection— such as in America— the panic is even further intensified. There it finds its best feeding grounds; and it is propagated through networks that operate at the speed of light. The need to hear the news several times a day is already a sign of fear; the imagination grows and paralyzes itself in a rising vortex. The myriad antennae rising above our megacities resemble hairs standing on end— they provoke demonic contacts.

And would any among us deny the almost prophetic foretelling of the postmodern age? Jünger seems to see instinctively, in the form and construction of postwar liberal society, the coming of the internet age — and the mass hysteria of “American Catastrophising— the constant hyping and hyperbolisation of everything” as our acquaintance Duncan Reyburn says.3 Conscious recall away from that regime of narrative domination is what becomes necessary.

Even assuming the worst possible scenario of total ruin, a difference would remain like that of night and day. The one path climbs to higher realms, to self-sacrifice, or to the fate of those who fall with weapon in hand; the other sinks into the abysses of slave pens and slaughterhouses, where primitive beings are wed in a murderous union with technology. There are no longer destinies there— there are only numbers.4

Here we have the ultimate rejection of nihilism; that there is a fate worse than death, and that we should never settle for being less than we are. Human dignity compels human will, with a divine mandate.

Perhaps only one in a hundred is capable of a forest passage. But numerical ratios are irrelevant here— in a theater blaze it takes one clear head, a single brave heart, to check the panic of a thousand others who succumb to an animalistic fear and threaten to crush one another.

In speaking of the individual here, we mean the human being, but without the overtones that have accrued to the word over the past two centuries. We mean the free human being, as God created him. This person is not an exception, he represents no elite. Far more, he is concealed in each of us, and differences only arise from the varying degrees that individuals are able to effectuate the freedom that has been bestowed on them. In this he needs help— the help of thinkers, knowers, friends, lovers.5

God created us to live among one another and for one another, in this we need help, one another, to realize ourselves as we are and were meant to be. This help in self-making comes from our friends and our lovers, not from programs or assigned case workers. This techno-bureaucratic system is one of domination and alignment, not of human flourishing. In this passage through we follow Christ our Savior.

To overcome the fear of death is at once to overcome every other terror, for they all have meaning only in relation to this fundamental problem. The forest passage is, therefore, above all a passage through death. The path leads to the brink of death itself— indeed, if necessary, it passes through it. When the line is successfully crossed, the forest as a place of life is revealed in all its preternatural fullness. The superabundance of the world lies before us.

Every authentic spiritual guidance is related to this truth— it knows how to bring man to the point where he recognizes the reality. This is the most evident where the teaching and the example are united: when the conqueror of fear enters the kingdom of death, as we see Christ, the highest benefactor, doing. With its death, the grain of wheat brought forth not a thousand fruits, but fruits without number. The superabundance of the world was touched, which every generative act is related to as a symbol of time, and of time’s defeat. In its train followed not only the martyrs, who were stronger than the stoics, stronger than the caesars, stronger than the hundred thousand spectators surrounding them in the arena— there also followed the innumerable others who died with their faith intact. To this day this is a far more compelling force than it at first seems. Even when the cathedrals crumble, a patrimony of knowledge remains that undermines the palaces of the oppressors like catacombs… With this blood, substance was infused into history, and it is with good reason that we still number our years from this epochal turning point. The full fertility of theogony reigns here, the mythical generative power. The sacrifice is replayed on countless altars.6

A free life unlocks the superabundance of the world, a life off rails, one which can grasp deep meaning and in which memory is lived and continued. When we come to terms with dignified death as a step in the path of Christ we can make our own passage. The postmodern totalizing state understands that Christ’s vision of life, death and salvation unlock a propulsion for life and soul that exists totally beyond it and beyond power. One that’s generative power lay in the deepest reaches of the human soul and compels a love of life and human freedom incomprehensible to material liberalism.

This necessarily leads to the persecution of the churches. In the new state of affairs man is to be handled as a zoological being, regardless of whether the theories predominating at the time categorize him along economic or other lines. This leads first into zones of pure utility, thereafter to bestial exploitation…7

That this is the case today is now undeniable. The Church remains the only and last human institution, flawed in countless ways as humans are, but delivering still a message about people as such. The scientistic antihumanism that pervades our society dissects us just as Jünger warned; as nothing but zoological creatures. To be plugged in, measured, scaled, medicated. There’s a pill for that, sadness is just chemicals, man. A regime of absolute demoralization rules, a pure erasure of human experience par excellence.

[In] many people today a strong need for religious ritual coexists with an aversion to churches. There is a sense of something missing in existence, which explains all the activity around gnostics… This is the gullibility of modern man, which coexists with a lack of faith. He believes what he reads in the newspaper but not what is written in the stars.8

Postmodern man is empty in this way; animated by a human spirit repressed and condemned at every turn. He hates himself, and what he knows in his gut— he dismisses such feeling, once known as conscience, as primal animalism— but he loves what he reads on white papers of studies. His religion becomes ideology, placed everywhere and nowhere, constrained by no theology. Consequently, if postmodern man has no theology, what is the role of the theologian?

Theologians of today must be prepared to deal with people as they are today— above all with people who do not live in sheltered reserves or other low pressure zones. A man stands before them who has emptied his chalice of suffering and doubt, a man formed far more by nihilism than by the church— ignoring for the moment how much nihilism is concealed in the church itself. Typically, this person will be little developed ethically or spiritually, however eloquent he may be in convincing platitudes. He will be alert, intelligent, active, skeptical, inartistic, a natural-born debaser of higher types and ideas, an insurance fanatic, someone set on his own advantage, and easily manipulated by the catchphrases of propaganda whose often abrupt turnabouts he will hardly perceive; he will gush with humanitarian theory, yet be equally inclined to awful violence beyond all legal limits or international law whenever a neighbor or fellow human being does not fit into his system. At the same time he will feel haunted by malevolent forces, which penetrate even into his dreams, have a low capacity to enjoy himself, and have forgotten the meaning of a real festival… [Man] is suffering a loss, and this loss explains the manifest grayness and hopelessness of his existence, which in some cities and even whole lands so overshadows life that the last smiles have been extinguished and people seem trapped in Kafkaesque underworlds.

Giving this man an inkling of what has been taken from him, even in the best possible present circumstances, and of what immense power still rests within him— this is the theological task. 9

In this way, the greatest theological task becomes the life of Christian Exit, the life of the forest fleer, the rebellious passage taker. To live outside and to move beyond; to be real and to decide for oneself. This is why the greatest genuine opposition to the technological bureaucracy of the modern total state comes from the retreat to the real, and to the generation of alternative authority. As Marc Barnes so perfectly articulated in his latest piece, “It turns out that nothing about the desire to run an unchanged modern State as one of its interns—or even as its executive—puts you on a watchlist. Meeting a bunch of your neighbors in the woods to run drills, though—that does the trick. “You want to order the state to the natural and divine law? Go for it, champ!” “You want to pull your ten kids out of school? Yeah, we’re going to need to check on your facilities.”10 This is precisely why the precipice of opposition is the threshold of the family home.

An assault on the inviolability, on the sacredness of the home, would have been impossible in old Iceland in the way it was carried out in 1933, among a million inhabitants of Berlin, as a purely administrative matter. A laudable exception deserves mention here, that of a young social democrat who shot down half a dozen so-called auxiliary policemen at the entrance of his apartment. He still partook of the substance of the old Germanic freedom, which his enemies only celebrated in theory… If we assume that we could have counted on just one such person in every street of Berlin, then things would have turned out very differently than they did. Long periods of peace foster certain optical illusions: one is the conviction that the inviolability of the home is grounded in the constitution, which should guarantee it. In reality, it is grounded in the family father, who, sons at his side, fills the doorway with an axe in his hand.11

This is the spirit of a parochial resistance, one which does not cling to the forms of the deracinating mass society but which centers and focuses life and politics around the position and decision of every man. Christian society, Christian exit, is not performatively spoken it is spoken in performance. Infiltration of the forms of the bureaucratic state, the other oft-discussed mode of Christian politics, or say of neo-reaction, can become unacceptable.

As we see, predicaments arise that demand an immediate moral decision… Generally speaking, the institutions and the rules associated with them provide navigable terrain; what is legal and moral lies in the wind. Naturally, abuses occur, but there are also courts and police.

This changes when morality is substituted by a subspecies of technology, that is, by propaganda, and the institutions are transformed into weapons of civil war. The decision then falls to the individual, as an either-or, since a third position, neutrality, is excluded.12

At the point of the either-or there becomes no infiltration; you must execute the agenda or become criminal. Here, the infiltrator, who will not become criminal, can find solace only in mental reservation that he does not will as he acts. For the Christian, this cannot satisfy.

For we cannot limit ourselves to knowing what is good and true on the top floors while fellow human beings are being flayed alive in the cellar. This would also be unacceptable if our position were not merely spiritually secure but also spiritually superior— because the unheard suffering of the enslaved millions cries out to the heavens. The vapors of the flayers’ huts still hang in the air today; on such things there must be no deceiving ourselves.13

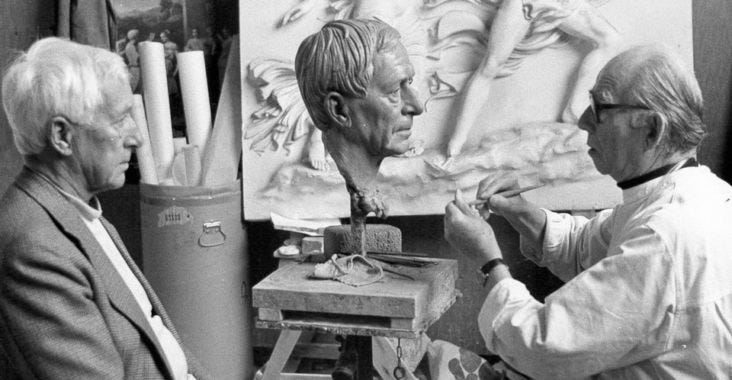

Ernst Jünger’s life was a human life in all its fullness; heroic action and deep meditation. A war hero, aesthete, entomologist, philosopher, author, and man. The alienation of postmodern life is a feature of the world built by liberalism and the orchestra of fear and narrative that surrounds us is a function of that system. Jünger broke out from that system, after living as its heroic image, he became the silent exiteer. You can see in The Forest Passage a flowering of a human spirit that transcends nihilism. There is no coincidence then that Jünger, two years before his death, after decades of his own lived discernment finally converted to Catholicism. We should all pray that we find the strength to live as he did, in an authentic, conscious life defined by position and decision.

Jünger, Ernst The Forest Passage. 1951 p.53

Jünger, Ernst The Forest Passage. 1951 p.27-28

Jünger, Ernst The Forest Passage. 1951 p.31

Jünger, Ernst The Forest Passage. 1951 p.32

Jünger, Ernst The Forest Passage. 1951 p.51

Jünger, Ernst The Forest Passage. 1951 p.54-55

Jünger, Ernst The Forest Passage. 1951 p.60

Jünger, Ernst The Forest Passage. 1951 p.62-63

Barnes, Marc Adrian Vermuele Against the World. New Polity, March 27th, 2023, https://newpolity.com/blog/an-overlong-screed

Jünger, Ernst The Forest Passage. 1951 p.73

Jünger, Ernst The Forest Passage. 1951 p.83

Jünger, Ernst The Forest Passage. 1951 p.33

Truly, Christ guides few of the blessed among the century through the forest passage. Great article- give unto your friends the lamp once shattered and walk with them through the mist.

I have been meaning to read The Forest Passage again for some time. I should get on that.