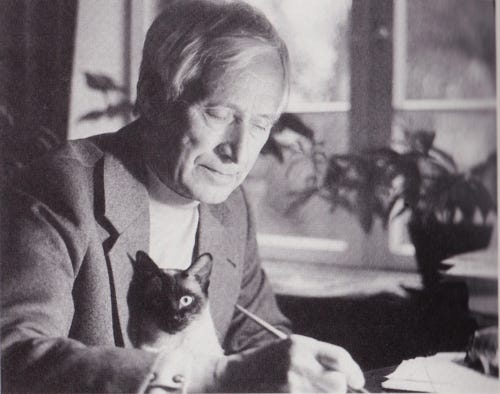

Once again it is Jünger Day; today marks the 129th year of a man who held so thoroughly, an Adventurous Heart. With his birthday coming during Holy Week, I thought it apt to tackle a topic which has long been the subject of my musing; the anarch as a Christian Image. Though Ernst Jünger’s full religious conversion did not happen for some decades after his first articulation of the Forest Rebel, an image which later develops into his ‘Anarch’, I believe it is a deeply Christian archetype. By this I do not mean that only the Christian can benefit from it, or even that it was Jünger’s intention to write to Christians specifically at the time of either the Forest Passage or Eumeswil’s publication. I mean however that the image of the anarch is, in its pedagogical value, one steeped deeply in the Christian political-philosophical tradition and its understanding of tyranny.

Tyranny

Tyranny, as understood in the Christian political tradition, is developed from Aristotle’s definition given in Book IV of the Politics. Here he defines the quintessential tyranny, that which is held directly contradistinct to kingship properly understood. Its defining characteristic is rule “with a view to its own advantage and not that of the ruled.”1 Or, as it has been aptly put, “rule for private gain.”2 For the Christian tradition, man is understood as naturally social, with politics arising organically from a pursuit between families, joined by marriage, of a common good grounded in love. The tyrant, then, is quintessentially tyrannical when he uses his rule not to organize towards the common good but merely towards his own benefit. Tyranny is deepened, as the Christian understands and Aristotle says, when he employs techniques of coercion to push those under him to pursue his aims instead of their common good- which they would not freely do. As Aristotle puts it, “Hence it [tyranny] is rule over persons who are unwilling; for no free person would willingly tolerate this sort of rule.”3

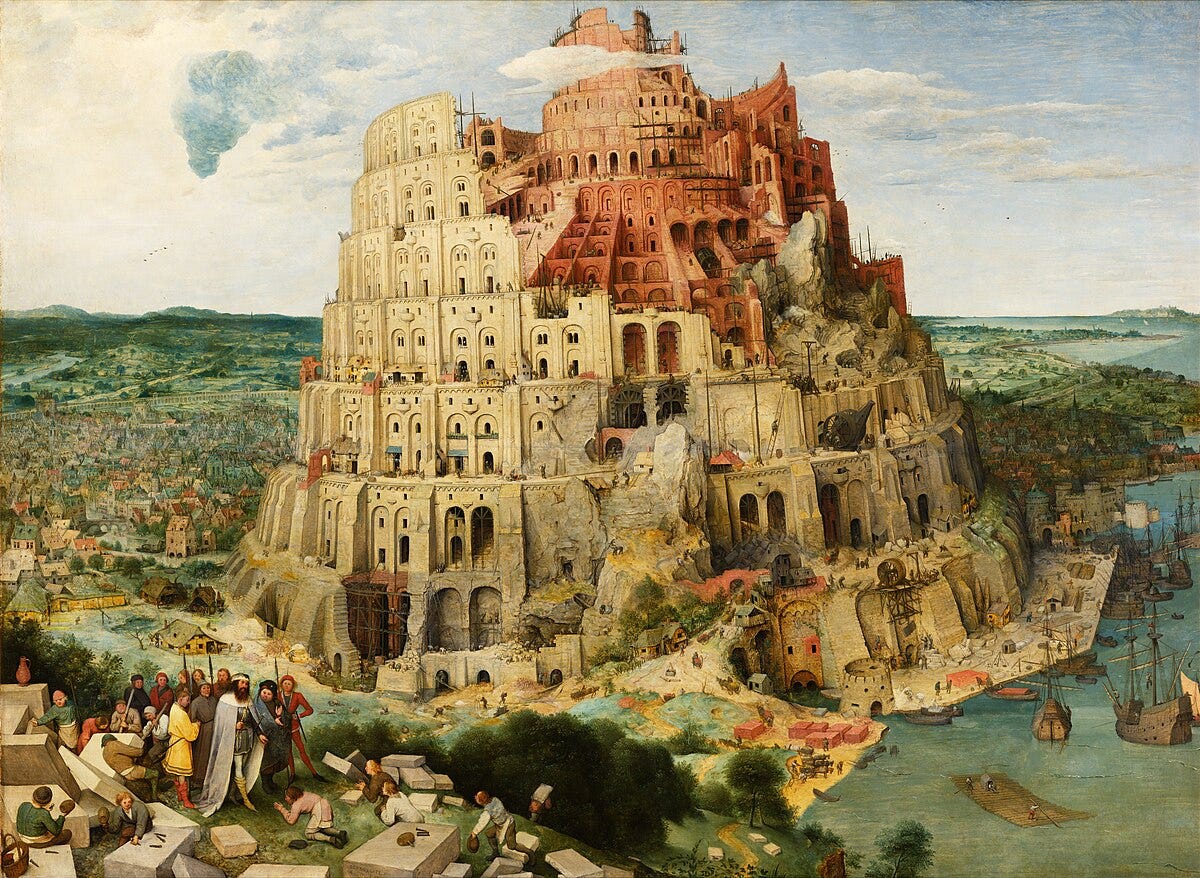

The archetype of the tyrant is found in Nimrod, the absolute ruler of the tower of Babel. Marc Barnes of New Polity discussed Nimrod and the Tower of Babel story in detail, drawing upon a reading of antique and medieval Jewish sources and commentaries on the story. I will confess now that I have not taken a deep dive into the rabbinical Old Testament commentaries, but I will defer to Barnes’ discussion as deeply illuminating on the topic of tyranny.4

New Polity discusses the introduction of anxiety into political rule as a prime way that a tyrant can coerce others to abandon working in for their own will, and to instead adopt the will of the tyrant, working towards the ends of tyrant instead of their own. Nimrod injects anxiety into politics by taking control of the children born into the families of Babel. Control of children must be recognized as coercive; when someone has your children, you do what they say. Control of language is another technique of tyranny; in Babel, everyone speaks the same language, and communicate in few words. This gives the tyrant the ability to control the definitions and use of words, controlling the frame from which the people can even conceptualize the topics at hand. In Babel, the final corruption of society comes from the treatment of people as below materiel. It is said that those who went against the regime were used as fuel to burn the furnaces that produced the bricks; when a laborer would fall from the tower, the others remained silent, but when a brick would fall, they would weep.

The 20th Century was rife with examples of tyranny, as the 21st century is now. Tyrants work to produce anxiety onto their populations, to control the flow of language and of information, and to use bureaucracy to dehumanize people down from embodied souls to commodities which can be identified by number and abstracted to mere ‘materiel’. Jünger himself was a close witness to the tyrannies of the 20th century; Bolshevism, Nazism, and then the tyranny of liberal democracy in the postwar era. Jünger recognizes that fear is a prime weapon of the tyrant, saying that the primary goal of domestic surveillance is the creation of fear and anxiety;

“Now an eye must be kept on everyone. The reconnaissance effort drives its organs into every city block, into every dwelling. It even tries to infiltrate the family, and its victories come in the self-incriminations of the great show trials: we see the individual stepping up as his own policeman and contributing to his own elimination. No longer is he indivisible, as in the liberal world; rather, he is dissected by the state into two halves— a guilty one, and another that denounces itself.”5

Fear is not merely today, however, a product of direct surveillance. Today fear and anxiety are the principle products of the media, and their corralling effect is undeniable.

Where the automatonism increases to the point of approaching perfection— such as in America— the panic is even further intensified. There it finds its best grounds; and it is propagated through networks that operate at the speed of light. The need to hear the news several times a day is already a sign of fear; the imagination grows and paralyzes itself in a rising vortex.6

Jünger recognizes that fear is a product that serves and reinforces tyranny, and so the regime benefits not only by appearing to ‘own’ fears but also by their production.

“Aiming simply to become more dangerous than one’s feared opponent leads to no solution— this is the classic relationship between reds and whites, reds and reds, and tomorrow perhaps between whites and non-whites. Terror is a fire that wants to consume the whole world. All while the fears multiply and diversify. The ruler by calling proves himself by ending the terror.”

It is in these passages that the true thesis of the Forest Passage is articulated; we must conquer the injection of anxiety and fear into every interaction, and we must reassert ourselves as real beings, real men and women with real dignity and real value.

If, on the other hand, the fear can be forced back into a dialogue, then man can have his say… The one path climbs to higher realms, to self-sacrifice, or to the fate of those who fall with weapon in hand; the other sinks into the abysses of slave pens and slaughterhouses, where primitive beings are wed in a murderous union with technology. There are no longer destinies there— there are only numbers. To have a destiny, or to be classified as a number— this decision is forced upon all of us today”7

The Anarch

The re-assertion of our dignity, our value, is a fog worth wading into. Jünger’s anarch, being a figure, whose mind is never captured, is almost a hero through his continued endeavor of existence. Eumeswil is set in the sands of North Africa, and I suspect that putting the anarch in the desert was an intentional move.

The man bound-yet-unbound to kingly authority is liberated as John the Baptist outside of the walls, Simeon atop the mighty column, or the monks of the Egyptian desert seeking God above all else. Throughout the existential postwar writings, Jünger casts first forest rebel and then anarch as man within society but not of society, a man who must cut through propaganda, lawfare, and deracination. In his Forest Passage, the anarch moves as an individual but is not solitary; “he needs help— the help of thinkers, knowers, friends, lovers.”8 As we have explored in the past, he needs also the help of the theologian and the priest.

This image of the anarch as the man on a journey to engage without coercion, to approach politics and rule as an equal and not a beast to be herded is on clear display in the characters of Jünger’s postwar fiction. There is an intense demand for intentionality and chosenness, not a rejection of duty but of locating duty from self-assignment; “the anarch wages his own wars, even when marching in rank and file.”9

This self-assertion cannot be minimized to a commitment to mere freedom, as the libertarian or the partisan sees it:

“the difference between the forest fleer and the partisan: this distinction is not qualitative but essential in nature. The anarch is closer to Being. The partisan moves within the social or national party structure, the anarch is outside it. Of course, the anarch cannot elude the party structure, since he lives in society.”10

An Augustinian disposition to the flawed nature of national political movements is available to the anarch when he realizes the postmodern predicament;

“My current situation is that of an engineer in a demolition firm: he works with a clear conscience insofar as the castles and cathedrals, indeed even the old patrician mansions have long since been torn down. I am a lumberjack in forests with thirty-year cutting cycles: if a regime holds out that long, it may consider itself lucky.

The best one can expect is a modest legality— legitimacy is out of the question. The coats of arms have been robbed of their insignia or replaced by flags. Incidentally, it is not that I am awaiting a return to the past, like Chateaubriand, or a recurrence, like Boutefeu; I leave those matters politically to the conservatives and cosmically to the stargazers.”11

The anarch is called to a radical reorientation of life away from the mass, from the abstract, the nihilistic or the bourgeois and towards the immediate, the proximal, and the spiritual; in this way the anarch treats the spiritual as an event of the heart, and not only the event of another plane; again, Augustine appears in the imagination.

Reorientation cannot be understood as resignation of all value, or a declination to recognize the other. Just as the anarch needs the help of friends and lovers, he owes them help as well.

“I would have ignored a crime [to not act] and neglected my first duty to my neighbor. From there to inhumanity is only one step. In any case, my situation was critical… ‘Don’t even begin to ignore’. . . This was the dictate of prudence.”12

Indeed, mere recognition of non-participation is utterly unsatisfactory, “we cannot limit ourselves to knowing what is good and true on the top floors while fellow human beings are being flayed alive in the cellar.”13 I have discussed at length elsewhere the anarch’s attachment to friends and family, and so I will suffice to say that while the anarch embodies a radical skepticism towards political movements, state apparatuses and corporate bodies, he conversely is totally immersed in the real. He can be more alone or more embedded, but given Jünger’s comments on the need for the help and to help others, social isolation is no more than a last desperate act. In Eumeswil, Martin is most alone of the anarch-examples because of what he sees as the total end of all sincere values inside of Eumeswil. In The Glass Bees, Captain Richards retains genuine connection to his friends and a total devotion to his loving and likewise devoted wife.

The end of the anarch is a redemption of life in the face of postmodernism through a total assumption of will, and an enduring cognizance of what is means and what is ends; life in society necessitates both. We might understand the supreme value of the anarch, articulated by Jünger through the analogy of the historian, as probity— radical self-honesty.

Through probity man can step back from the clutches of the tyrant and the reach of propaganda, he can view his regime, society, community not through the lens of political movements or ideological systems but of concrete and discrete action. It is in this sense that the anarch frees himself from tyranny, through an overcoming of fear and nihilism both, and then returns to society through love and obligation to others and to transcendent value. The perspective of the anarch then is never adversarial towards the regime, but merely ambivalent to its ends. Insofar as the regime is good, then, the anarch is in alignment— insofar as the regime is tyrannical, the anarch moves through and over the line.

Saint Augustine

Those who have read St. Augustine surely by now have had his reflections on the heart and soul in mind. I would like to make two short connections with the City of God to sketch a connection between these thinkers.

In Book I Chapter 35, St. Augustine discusses the nature of the two cities, and the opacity through which we approach each. In their most distinct form, we understand that the City of God exists in Heaven and the City of Man here on Earth. Less concretely, though we know the City of God is found in the Church and the City of Man in the State. Finally, St. Augustine observes that the City of God and the City of Man are likewise written on the hearts of each man; we often do not know whether any given man truly dwells in one or the other.14

Broadly, throughout the City of God, Augustine makes clear that he is largely ambivalent towards the particular policies or structures of a regime, so long as it is oriented towards truth and virtue, through true love commonly held. Likewise, the anarch is ambivalent to the particular structures of regimes, and much more interested in the discrete content of their actions, either for common good or mere private gain.

In this way, the anarch’s call to probity through distance and reflection followed by his radical embrace of responsibility and presence of will, coupled with the embrace of the duty to care creates of the anarch a truly Christian pedagogical symbol. When we add Jünger’s own reflections on the critical role for priests and theologians, we can understand the anarch as a man confronting the postmodernity of man and recapitulating the value of his life entirely to the real and divorced from the tyranny of anxiety.

Forest Rebel, Anarch

In the limited scholarship around Jünger’s postwar writing, there is a tendency to draw a bright-line distinction between the literary figures of the Forest Rebel and the Anarch. I have chosen not to do this— though I reserve the possibility of doing so in the future. Here, my intention was to show how the themes of the literary figures in Jünger’s postwar writing lead towards this deeply Chirstian pedagogy; in the same way that Jünger himself developed towards his own final culmination in the faith, absolutely the figures of his literary existentialism evolved. For the discussion on this topic, though, they are too connected to benefit from such a clean distinction.

Ernst Jünger’s Birthday

It should be clear so far, over a year into this project and with a second ‘Jünger Day’, that Ernst Jünger is a heroic figure in my eyes. To be more blunt— to me he is a hero. Imperfect as all mere men are, he reached to superhuman heights in his life and was not content to merely exist as an example but had an immensely rich drive to share his perspective, feelings, and insights with us in the form of his fiction. We should be deeply grateful for that.

Sanfedisti

Aristotle, Politics, trans. Carnes Lord University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London 2013. p.114 4.10

Jones, Andrew Willard & Marc Barnes. “Politics of Tyranny” New Polity. Youtube.

Aristotle, Politics, trans. Carnes Lord University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London 2013. p.114 4.10

Jones, Andrew Willard & Marc Barnes. “Politics of Tyranny: How Tyrants use Scale” New Polity. Youtube.

Jünger, Ernst The Forest Passage, trans. Thomas Friese. Telos Press Candor, New York. trans. 1980.

Jünger, Ernst The Forest Passage, trans. Thomas Friese. Telos Press Candor, New York. trans. 1980. p. 29

Jünger, Ernst The Forest Passage, trans. Thomas Friese. Telos Press Candor, New York. trans. 1980. p.31

Jünger, Ernst The Forest Passage, trans. Thomas Friese. Telos Press Candor, New York. trans. 1980. p.32

Jünger, Ernst Eumeswil trans. Joachim Neugroschel, Telos Press, Candor, New York 2015. p.106

Jünger, Ernst Eumeswil trans. Joachim Neugroschel, Telos Press, Candor, New York 2015 p.107

Jünger, Ernst Eumeswil trans. Joachim Neugroschel, Telos Press, Candor, New York 2015 p.75

Jünger, Ernst The Glass Bees trans. Louise Bogan & Elizabeth Mayer, New York Review Books. New York, New York. p.159

Jünger, Ernst The Forest Passage p.33

Augustine, City of God, trans. Dyson, R.W. Cambridge University Press, 1998.

I accidently liked this article before reading it. Then I read it, and as I was reading, I was thinking, "Yeah, pretty good article here." And then you connected the symbol of anarch to Augustine, and I thought, "Now he's cooking with gas!"

Beautiful San.