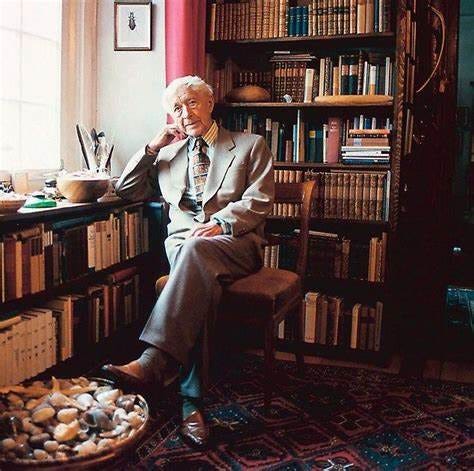

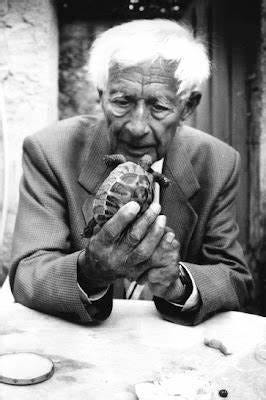

I have read nearly every word Jünger has ever written (that's made it into English, which is likely less than half) as well as his correspondences with Carl Schmitt, the most important political theorist of the twentieth century, and Martin Heidegger, the most important Philosopher (Straussians on suicide watch) of the twentieth century, both of whom he happened to be close lifelong friends with. It's no surprise given his century spanning life and incredible personal journey that he's a man with a lot to say, and a lot worth listening to.

As a novelist and essayist for nearly his entire life, however, that's a lot of text. It's a corpus that is at best daunting and at worst borderline inaccessible, especially to English speakers, who are still lacking translations to key pieces of his work. In this essay, I will lay out two approaches to reading Jünger's work and make suggestions for when to take each route. I will also discuss the problems with attempting to read Jünger as an English speaker and attempt to cross those bridges for the benefit of my readership.

A brief overview of the philosophical trajectory of Ernst Jünger.

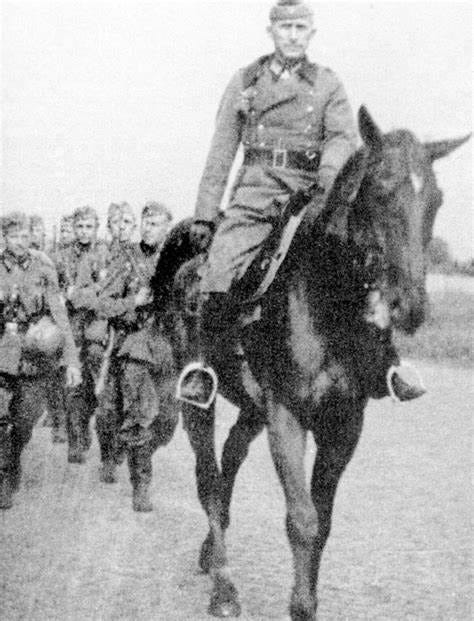

As a teenager, Jünger fights through the first world war as a volunteer fusilier and then as a stormtrooper commander. He publishes his memoir of the war, Storm of Steel, to wide acclaim. This book was seen as squarely in the Nietzschean frame, as his testimony to it afterwards confirmed.

During the Weimar period, Jünger becomes the editor of various right-wing and revolutionary political journals, he becomes known as a virulent anti-democrat. Seen as an important figure in the Weimar-era 'Conservative Revolution', he becomes disillusioned with politics during this period.

In 1932 Jünger publishes 'Der Arbeiter. Herrschaft und Gestalt' translated to English was 'The Worker: Dominion and Form'. This ambitious project tackles the metaphysical consequences of 'total mobilization' through industrial society, a now famous term he coins. It is seen as his departure point from Nietzschean thought. This book was seen widely as offering a worldview incompatible with Nazism, and the book was reviewed unfavorably by the NSDAP. At the same time, Martin Heidegger's attempt to teach a seminar on the book was first harassed and then finally shut down by the police.

On the day of the invasion of Poland, Jünger publishes 'On the Marble Cliffs', a work of fiction that explores themes of resistance against tyranny. 30-some-thousand copies are printed before further publication is banned. Later in the war, one of Jünger's sons, Ernst, is taken to Carrara in Italy by the SS, a rural mountain village known for its 'Marble Cliffs', where he dies (almost certainly assassinated by the SS).

Throughout his stay in Paris during the war, Jünger feels called the read the Bible in its entirety. War ongoing, he and his friend Erwin Rommel join Claus von Stauffenberg's now infamous failed plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler. Jünger is charged with drafting the peace document to be offered to the Western Allies upon the success of the plot. Published after the war's conclusion and titled 'The Peace' it is a wide diversion from his previous work. The document is deeply humanistic, religious, and advocates for the creation of a kind of proto-European Union united around a strong Church. There is no doubt in my mind, although this is my own conjecture, that this direction was influenced both by Stauffenberg's outspoken political Catholicism, and the plot's deep connection to Pope Pius XII who was the plotters’ intermediary to the Western Allies.

After the war, Jünger was banned from publishing for 5 years by the occupying allied government for refusing to submit to de-Nazification programs. When he was again able to publish, and for the rest of his life, his political work tended to be concerned with personal resistance against and overcoming of tyrannical regimes of various types. In Heliopolis he deals with civil conflict and political violence, in The Glass Bees he deals with democratic capitalism and postindustrial society, and in Eumeswil he deals with living in a modern secular state after revolution. The Central figure of this era can be called 'The Anarch' though throughout the course of this decades long period it evolves somewhat, earlier being described as the ‘Forest Rebel'.

Jünger officially converts to Catholicism after engaging with the idea since the second world war, two years before his death. At this time he is no longer writing.

The central theme of Jünger's political writing seems always to be the transformation of the individual to a greater state. At the beginning of his life, this comes through the clash of metal and the thunder of war, understood as a deeply felt self actualization caused by triumph of the spirit against all odds. After the war, in recognition of the technologized and totalizing world that had been created by the transformation of mass industrialization across all facets of society, he grappled with how the form of man would be changed by this new world. First, man was to be liberated into a higher state, a more powerful and more capable universal form of the Worker. But as time passed, the optimistic stance of the Worker fades. We must prepare ourselves for a life alienated by technology and by tyranny. Following the war, this quest to realize oneself becomes concerned with the absolute and all encompassing 'soft' tyrannies of democracy and liberalism, which deracinate, alienate, suppress, and debase those within their orbit. How to be free; not libertine, but free to be noble and great, truly free, truly excellent, remains constantly the northern star of his thinking.

The problem with reading Jünger

The problem with reading Jünger to me appears to be two-fold. The first is that the corpus of his work is so large that to commit to reading it fully may end up with the reader coming away with a warped view of his conclusions, if they do not see through the entire arc of his writing or if they do not keep a proper order of approach. The second problem is that key texts in each distinct 'period' are left entirely untranslated into English and so important bridging material is unavailable.

For example, it is suggested that On the Marble Cliffs, Heliopolis and Eumeswil are best understood as a trilogy; unfortunately, it is hard to assess the works as a trilogy, as the middle book, Heliopolis, remains unavailable in English. Likewise, Gardens and Streets, considered to be an important piece of his thought in opposition to Nazism and published in 1942, remains untranslated. This important link between 'The Worker' or 'Marble Cliffs' and 'The Peace' is therefore inaccessible to English readers, complicating our ability to understand his wartime transformation. And finally, his essays which explain, expand on, and show the shifting attitudes towards his (failed and eventually abandoned) techno-optimism in The Worker, 'At the Timewall' and 'The World State’ remain likewise inaccessible to English audiences. In total, this constitutes a significant problem to a full understanding of Jünger's philosophical trajectory and makes particularly opaque the transition periods between different eras of his thinking.

Reading Jünger

I will offer two approaches to reading Jünger's work. One will be for those who wish to read his full corpus, and the second will be for those who wish to take a more casual approach, digesting his most important works and then moving on in small blocs. It is my suggestion that most people begin using the second method, complete the entire 'core’ bloc and then decide whether to restart to pursue his entire complete works or to continue to different themed blocs. Books which are worth reading but not “core” will be marked by asterisk. Currently untranslated works will have a double asterisk. Books and essays that the casual or even interested reader have little hope of acquiring are left off the list entirely.

A ‘Complete’ Reading Order:

Storm of Steel

*On Pain

*War as an Inner Experience

*Copse 125

*Fire and Blood

*Sturm

The Worker

*German Officer in Occupied Paris

**Gardens and Streets

The Peace

**At the Timewall

**The World State

Friedrich Georg Jünger's “The Failure of Technology”

*On the Marble Cliffs

**Heliopolis

The Forest Passage

The Glass Bees

*Aladdin's Problem

Eumeswil

Additional Texts & Resources:

*Correspondence with Martin Heidegger

*Martin Heidegger's 'On Ernst Jünger'

*Alain de Benoist's ‘Ernst Jünger'

*The Adventurous Heart

*Approaches

*Visit to Godenholm

*A Dangerous Encounter

*The Tree

'Casual' Recommendations:

“Core" Books

The Forest Passage

The Glass Bees

Eumeswil

*You may add 'On The Marble Cliffs' to the beginning of this list. I have left it off because the book is challenging to read, its prose is opaque, surreal and borderline fantastical. It is difficult, and the casual reader may glean a sufficient understanding of Jünger's position without it, though certainly more dedicated minds would benefit from reading.

**You may swap The Glass Bees and The Forest Passage here if you have a strong preference for fiction novels over nonfiction essays, but you should read it before diving into Eumeswil.

Subsequent Blocs, to be read in whatever order pleases you;

War:

Storm of Steel

On Pain

War as an Inner Experience

Psychedelics:

The Adventurous Heart

Approaches

Visit to Godenholm

The Worker & Following:

The Worker

Alain de Benoist's ‘Ernst Jünger'

**At the Timewall

**The World State

The Peace

Friedrich Georg Jünger's “The Failure of Technology”

Correspondence and Related Writings:

German Officer in Occupied Paris

Martin Heidegger and Ernst Jünger Correspondence

Martin Heidegger's 'On Ernst Jünger'

Thank you for reading Position & Decision! I was inspired to put together an article like this following the great engagement and the huge numbers of questions surrounding this topic that we got during our open 'Ask Me Anything’ on Twitter.

I wanted to force subscription to the substack in order to actually view the reading lists but after five or so minutes looking for a way to do that which didn't involve asking anyone to pay, I gave up. Please consider subscribing and sharing this despite our open platform! It really helps us guage interest in the work.

That's a really good summary of Junger and his work. This is a golden era for Anglophone Junger studies - new translations keep coming out.

I do get the impression that the readability of his work goes down through his career, with the earliest writings being the most accessible.

I did enjoy reading "the Details of Time" but find some of the interviews and conclusions journalists make in the latter stages of Junger's life quite odd. They take at face value a man who spent years writing about inner freedom and his concept of the Anarch.

I'd always put Storm of Steel as top of the recommendations list, as it's the best known and most accessible of Junger's works, even if in many ways it's the least typical piece.

Great article and primer on Jünger, certainly one of the most unbiased and straightforward overviews of his trajectory. The recommendations list is the best that I've seen so far. Keep up the good work!